Publisher's note: This post appears here courtesy of the Carolina Journal, and written by Mitch Kokai.

As a big fan of

redistricting reform, this observer appreciates hearing support for the cause from Wake County Superior Court Judge Paul Ridgeway.

As an even bigger fan of our constitutional government's separation of powers, I would have preferred to have heard Ridgeway's comments under different circumstances.

"It is the court's fervent hope that the past 90 days becomes a foundation for future redistricting in North Carolina and that future maps are crafted through a process worthy of public confidence and a process that yields elections that are conducted freely and honestly to ascertain fairly and truthfully the will of the people," said Ridgeway from his judicial perch on Dec. 2. He was reading a statement endorsed by Judges Alma Hinton, a fellow Democrat, and Joseph Crosswhite, a Republican.

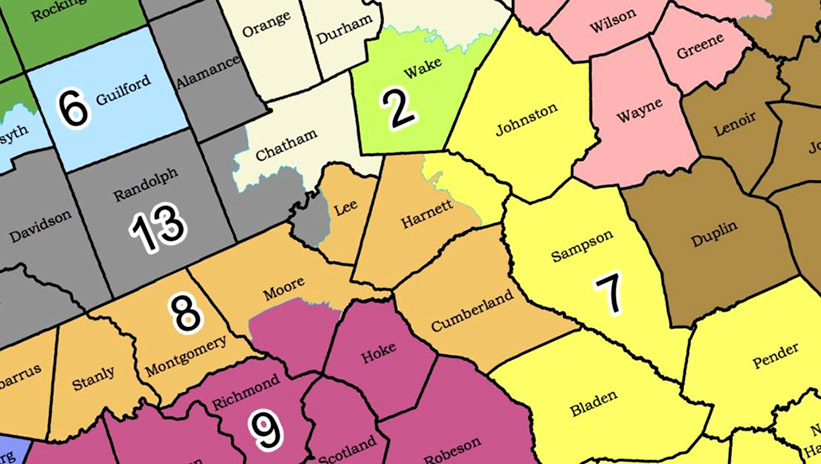

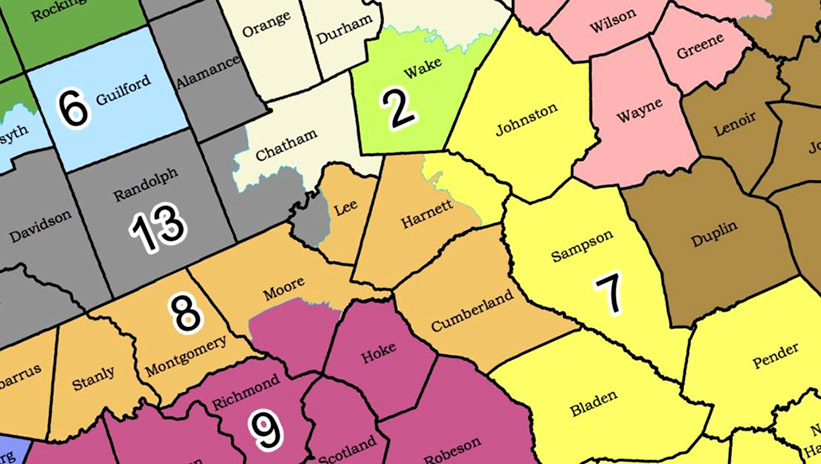

That endorsement of a better electoral mapmaking, or redistricting, process followed roughly three months of courtroom action. In those 90 days, Ridgeway and colleagues threw out state House and Senate election maps. They threatened to do the same with the state's congressional map. And they both ordered and cajoled state lawmakers to overhaul decades-old procedures used for drawing state election lines.

There's near-universal agreement that the process used to comply with the court's orders turned out better than redistricting procedures employed by any previous set of N.C. state lawmakers - Republican or Democrat.

But at what cost? The judicial branch of government essentially told the legislative branch how to do its job. That's not supposed to happen in our system of government. When it does happen, there must be clear guidance from the constitutional law that governs both branches.

By failing to set out clear standards explaining their extraordinary actions, the judges have set the stage for future legal action. The next time someone feels aggrieved by electoral mapmaking in North Carolina, he'll have an incentive to run to court. The three-judge panel's actions have done nothing to shut the door on future lawsuits.

Before amplifying my concerns, it's important to note that I agree with Ridgeway and colleagues about improvements in the redistricting process over the 90 days: live video and audio streams, restrictions on use of prior election results for new maps, all mapmaking decisions in full public view.

These are all laudable developments. Some mirror redistricting reforms the John Locke Foundation has endorsed for decades. But calls for reform have targeted the legislative branch. Lawmakers hold the constitutional power to redraw election lines. They should be the ones to enact changes improving the process.

Electoral mapmaking reform is not a proper job for judges.

After decades of inconsistent pronouncements on the topic, the U.S. Supreme Court agrees. Last summer the high court decided federal judges no longer would play any role in partisan fights over election mapmaking. If the federal government is going to address the issue, justices ruled, it's a job for Congress. In other words, it's the legislative branch's issue.

That U.S. Supreme Court ruling in

Rucho v. Common Cause did not shut the door on state court consideration of electoral mapmaking. But it should have convinced state-level judges that courts ought to avoid disputes that focus more on political preferences than legal principles.

To be fair, Ridgeway and his colleagues believe they did stick to legal issues. They agreed with Democrats who challenged state election maps as examples of "extreme" partisan gerrymandering. So extreme, according to the argument, that the maps violated multiple provisions in the N.C. Constitution.

It's unfortunate for all concerned that, while making that legal determination, the judges never set a definition or standard for "extreme." Rather than attempting to distinguish between constitutionally acceptable and unacceptable levels of partisanship in electoral mapmaking, the judges seemed to rely on the Potter Stewart standard. Stewart was the U.S. Supreme Court justice who quipped in a 1964 obscenity case:

"I know it when I see it."

Given the lack of a clear standard, it's unsurprising that Democratic challengers continued to label new maps "extreme," even after Republican legislative leaders employed a more open, transparent mapmaking process. If no one really knows what constitutes "extreme," Democrats seeking to maximize their partisan advantages had strong incentives to push for maps that might yield even better outcomes for them.

The electoral clock ultimately

prompted an end to this chapter in the state's ongoing redistricting fight. Judges did not want to continue haggling over the issue as candidates started filing for office.

But nothing within the law is settled. Without an agreement among legislators on a new procedure, it's likely that maps drawn with new census data in 2021 will head back to state court. One party almost certainly will argue that those maps are "extreme" and thus unconstitutional.

Absent a clear standard defining "extreme" unconstitutional mapmaking, North Carolina could face another decade of prolonged courtroom fights. No one should desire that outcome.

Reacting to Ridgeway's "fervent hope" for redistricting reform, Jane Pinsky of the N.C. Coalition for Lobbying and Government Reform responded:

"In the next year, we will work together to pass legislation that will give North Carolina a transparent, open, nonpartisan redistricting process that has strong citizen involvement."

The key words in her statement: "pass legislation." That's crucial. Reform ought to take place in the halls of the state Legislative Building, not in a courtroom.

Mitch Kokai is senior political analyst for the John Locke Foundation.