Publisher's note: We believe the subject of history makes people (i.e., American people) smarter, so in our quest to educate others, we will provide excerpts from the North Carolina History Project, an online publication of the John Locke Foundation. This one hundred and twentieth installment, by Mathew Shaeffer, is provided courtesy of the North Carolina History Project, and re-posted here with permission from NC Historic Sites.

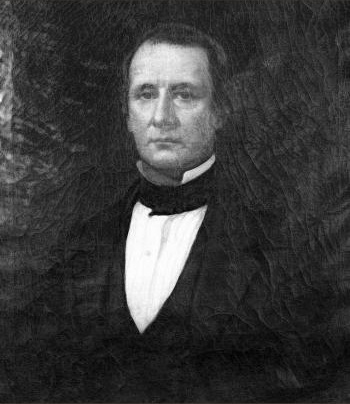

Josiah Collins III, Image courtesy of the North Carolina Department of Archives and History

Josiah Collins III was born in Edenton, North Carolina in March 1808.

The son of Josiah Collins II and Ann Rebecca Daves, he spent his early years in

Edenton where his grandfather,

Josiah Collins, Sr., established a shipping empire and

ropewalk. He was later educated at Harvard and then studied law at Litchfield, Connecticut. His short residence in New York City cultivated a love of large parties and the opera.

In August 1829 after finishing his education, Josiah Collins III married Mary Riggs from New York. The newlyweds arrived at Somerset Place in

Washington County, North Carolina on January 5, 1830 and became the first members of the Collins family to establish permanent residency at the plantation. Previously the plantation had been part of his grandfather's

Lake Company and remained a side business for the Collins family. A few years before Collins III moved to Somerset, his father Josiah Collins II prepared the plantation for his son. Collins II increased the number of slaves, improved the plantation's infrastructure, and built the "Colony House" as the dwelling for the newlyweds. Unhappy with the small Colony House, Josiah Collins III constructed a much larger dwelling, the Collins Mansion (or Mansion House). Finished in 1830, the mansion still stands today as part of the Somerset Place Historic Site.

The Mansion House was the center of Collins's lavish and ostentatious lifestyle. Josiah Collins III was described as having an "aggressive type of hospitality" that some considered absurd. Collins's domineering personality influenced others to participate in his grandiose lifestyle. Collins rarely stayed at Somerset during the summer months, but while there, he threw lavish parties and entertained numerous guests (a typical winter saw about fourteen long-staying guests). In the spring of 1857, it is said that there were quadrilles (a square dance consisting of four or more couples) every night.

Collins enjoyed and took great pride in cultural pursuits. In 1845 he attempted to make French the language of the Collins household and hired a tutor to teach the family French. He also purchased a piano for his sons. Collins enjoyed reading and spent time reading out loud to his family and the neighboring children. From 1855 to 1860 he even organized a Monday night reading club that featured reading out loud, discussions, and musical interludes.

To support his extravagant lifestyle, Collins relied heavily on the income from Somerset Place. Collins, one of the three largest slaveholders in North Carolina, turned the plantation into one of the largest and most diverse in North Carolina and the upper South. Somerset originally consisted of over 100,000 acres of land, but the land was divided among children of Josiah Collins II at his death in 1839. By the 1860s, Somerset consisted of 14,500 acres (about 2,000 acres cultivated), housed 328 slaves, and included over 50 structures (including a hospital, a kitchen complex, a laundry, and a dairy). The primary crop produced was corn, but the plantation also produced wheat, peas, beans, potatoes, sweat potatoes, oats, flax, wool, butter, milk, and silk. According to the 1860 census, the plantation had 42 horses, 55 mules, 30 oxen, 55 cattle, 52 milk cows, 225 sheep, and 496 swine. Somerset relied heavily on its slave population to clear and cultivate the land. Collins provided adequate food and shelter for the slaves, and he even kept a detailed daily record of the tasks assigned to slaves.

Like his father, Collins was very religious. He became especially interested in the religious life of the slaves and frequently read them Episcopal services. In 1836, Josiah Collins III built a chapel on his land and hired E.M. Forbes to convert the slaves from Methodism to the Episcopal Church, a process that took three years. Collins also hired his own private chaplain, and in 1857 Reverend George Patterson performed services in both the mornings and evenings at Somerset Place.

As tensions between the North and the South increased, Josiah Collins III became active in politics and passionately opposed abolitionism. Mrs. Pettigrew, the wife of Charles L. Pettigrew who owned the neighboring Pettigrew Plantation, wrote: "Our excellent neighbors appear to me as rabid on one side of the subject, as the Abolitionists are on the other." Collins took up public office, even though he had little desire for it, and was credited as being a "ready, skillful debater." He served in the North Carolina Senate as a Whig for two sessions (dates not listed), was a delegate from Washington County to the 1835 state constitutional convention, and served as the chair of the committee to arrange senatorial districts. In 1850, he unsuccessfully ran as a Whig from Washington County for the North Carolina House of Commons.

With the approach of the Civil War, Collins became increasingly moody and suffered frequent headaches. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Josiah Collins III personally funded and outfitted multiple companies of Confederate soldiers from Washington County. By 1862, the Union controlled Roanoke Island and most of the North Carolina Coastal Plain, and the Collins family fled to Hillsborough, North Carolina. There, they remained for the war's duration. During their absence, Union forces and desperate locals plundered Somerset Place, and farming on the plantation ceased. Collins died on June 17, 1863 in Hillsborough. Following his death and the conclusion of the Civil War, the Collins family unsuccessfully attempted to restore Somerset Place. They were forced to sell the property to creditors in 1867. Eventually Somerset Place was acquired by the state of North Carolina and has become a State Historic Site that emphasizes the role of slaves on southern plantations.

Sources:

William S. Tarlton, Somerset Place and its Restoration, (N.C. Division of State Parks: August 1, 1954). Copy found in the North Carolina Department of Archives and History: Josiah Collins Collection.

William S Powell, "Josiah Collins III" in Dictionary of North Carolina Biography Vol. 1 A-C, edited by William S. Powell (University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, 1979), 405-406.

North Carolina Historic Sites. "Origins of Somerset," North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, http://www.nchistoricsites.org/somerset/history-somerset.htm. Accessed on October 9, 2013.

North Carolina Historic Sites. "Origins of Somerset," North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, http://www.nchistoricsites.org/somerset/history-somerset.htm. Accessed on October 9, 2013.

North Carolina Historic Sites. "Somerset Place: A Timeline: 1850-1860," North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, http://www.nchistoricsites.org/somerset/people1850-1860.htm. Accessed on October 9, 2013.

North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program , "Somserset Place," North Carolina Office of Archives and History, http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=B-57, Accessed on October 9, 2013.